|

title unknown (detail)

What is a makam?

Oransay described makam (Turkish

makam, plural makamlar; Arabic maqam, plural

maqamat) as 'composition rules'. They are definite scales which are

governed by certain rules which we will talk about later. A makam

has no intrinsic (allegorical) value and is not bound to certain times of

the day or year, as is the related Indian raga. The makam names

designate an important note in the scale (i.e.

Turkish

Cargah, Arabic

Chahargah: fourth position), or a city

(i.e. Esfahan, it is

sometimes spelled as Isfahan), a landscape (i.e. Turkish

Hicaz, Arabic Hijazi), a person (i.e. Kurdi) or a

poetic abstraction (i.e. Suzidil: heart

glimmer).

Makam principally distinguishes the eastern classical

tradition from western musical practice. Based on the use of untempered

intervals (with as many as 53 microtones amplifying the western octave), a

given makam follows a particular scale and a set of associated

musical practices. Each makam joins a tetrachord (Turkish

dortlu), and

a pentachord (Turkish besli). Certain rules/characteristics of a

makam may include the entry tone (Turkish giris, Arabic

mabda), the final tone (Turkish karar, Arabic qarar)

which may or may not be the same tone as the entry tone, the leading tone

(Turkish yeden), dominant (Turkish guclu) and tonic (Turkish

durak), as well as stressed secondary tonal centers. The

seyir (path, way) (Arabic zahir) of a makam is

determined by the direction of the melody, which may be either ascending

(Turkish cikici) or descending (Turkish

inici) or a

combination of the two (Turkish inici-cikici).

Range (makam may be extended above and below the octave without

repeating), modulation, temperament, melody types, and cadential endings

(i.e. suspended cadences) may also determine a makam's make-up.

Compound makamlar

exist which combine elements from two

makamlar. Thousands of makamlar have been theoretically

conceived though only a few hundred have been used. Of these, about one

hundred have been fully developed into musical

settings.

The

computation of the exact sizes of the microtones and the notation of

makam are rather complicated, and several alternatives were

presented at the Cairo Congress on Arab Music in 1932. Some of the scale

systems discussed at this meeting were obtained through mathematical

computation and some were established experimentally. The most important

systems were those presented by representatives of the Royal Institute of

Arabian Music in Cairo, by Idris Ragib Bey and I. Shalfun of Egypt, by

Xavier Maurice Collangettes of the University of St. Joseph in Beirut, the

Turkish system of Rauf Yekta Bey from the Conservatory of Turkish Music,

and the system of Shaykh Ali al-Darwish (student of Rauf Yekta Bey). The

differences between theorists and musicians, as well as modern research on

the tonal structure of vocal and instrumental music indicate that none of

these systems provides an accurate description of actual musical practice.

They are merely convenient tools for prescriptive and didactic purposes.

Conservatories, musicians and theorists in different countries use

different scale systems which leads to the differences in the notations of

accidentals and makam names.

It is

impossible for us to explain all the different systems or makamlar.

In the "Music" section of this web-site, there are a few pieces by famous

Turkish composers. Because of our Turkish musical background and to

understand the accidentals and the pieces better we would like to say a

few words about the Arel-Ezgi system. In Turkey, Rauf Yekta Bey's work was

continued by Subhi Ezgi and Sadettin Arel. The system they came up with,

later know as the Arel-Ezgi system, is the most widely practised system

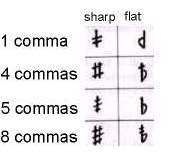

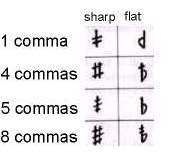

currently. The Arel-Ezgi system consists of a theory of intervals,

involving such discrete intervals as the koma (comma). Every whole

step is divided into 9 commas and accidental markings indicate raising or

lowering the pitch by 1, 4, 5, 8, and 9 (which is the double sharp/flat)

commas:

Reprinted from:

Kurt Reinhard: The

New Grove: Dictionary of Music and

Musicians. vol.

19. ed. London: Macmillan, 1980

Josef Pacholczyk: The

New Grove: Dictionary of Music and

Musicians. vol.

1. ed. London: Macmillan, 1980

Karl Signell: Makam: Modern

Practice

in Turkish Art Music. New

York: DaCapo Press, 1985

Walter Feldman: Music of the Ottoman

Court. Berlin: GAM- Media GmbH, 1996

|